“You seem to have a case of…being a man.”

I’m not going to talk about the Covington kids or MAGA hats or Gillette commercials; you can read more about them just about anywhere. I wanted to reflect on something that is supposed to be a shade more academic than all that, yet I haven’t seen too much commentary on it in these past few weeks of evidently poisonous men.

I’m not going to talk about the Covington kids or MAGA hats or Gillette commercials; you can read more about them just about anywhere. I wanted to reflect on something that is supposed to be a shade more academic than all that, yet I haven’t seen too much commentary on it in these past few weeks of evidently poisonous men.

It’s a real shame that it has taken this long to have concerted cultural conversation on masculinity and a bigger shame that it is being treated in this way. Men started having serious conversations about the meaning of being a man back in the ‘90s with Robert Bly and Iron John especially, but also from a host of other writers, many of them good Catholic men. Some of the excesses of that movement were lampooned in popular culture (shirtless middle-aged guys in the woods wearing war paint and beating drums, men hugging and crying like children because they were “allowed” to have feelings) and maybe rightly so. But there were also many important ideas that came out of that movement, most notably a sense that what it meant to be a man had been lost and that men were confused about who they were. Men were drawn to the movement because they knew they had something important to offer specifically because they were men, but that had become lost.

It’s even further lost now. Many men who actually care what other people in their lives think about them have become scared or embarrassed to act like a man, talk like a man, or even express that they like being men.

(For what it’s worth, I love being a man, and I encourage my two sons to love being men also.)

That’s all by way of reflection on the past. Now to what I mentioned in my first paragraph. The American Psychological Association this month released Guidelines for Psychological Practice With Boys and Men (though it is dated August 2018). It has missed the mark. I’m not especially surprised by this: the APA has not been a legitimate source for the truth about the human person for at least 50 years.

In fairness, the guidelines were intended as an overdue companion to their Guidelines for Psychological Practice With Girls and Women, released in 2007. But there can be no doubt that there is an ideological agenda at work in releasing these guidelines right now.

And what do they include? I encourage anyone interested to read the 36-page document themselves, though it’s a pretty frustrating read. One encounters problems right from the outset:

- On page 2, there is a need to define “cisgender,” “gender bias,” “gender role strain,” “masculinity ideology,” “oppression,” and “privilege.” The document’s landscape is defined by a host of ideological buzzwords before men themselves are even addressed.

- By contrast, these same definitions are included in the guidelines for women, but only after 11 pages of description of the situation of women in the world are provided first. In other words, there is a presumption about “women” that cannot be taken for granted for “men.”

- The guidelines strive to avoid stereotyping of women and the effects of bias on women. The first part of the guidelines for men instead state that there are competing masculinities. This calls into question the meaning of masculinity right from the start, which is not done for women.

- The guidelines for men question behaviors in which men act out against themselves and others, while the guidelines for women discuss behaviors that are done against women. I am willing to believe this was not entirely intentional, but there is a curious narrative here of men doing evil and women suffering evil in these documents.

In fairness, it’s not all horrible: the guidelines note that men die sooner, commit suicide more often, and engage in unhealthy lifestyle choices more regularly, and that these are serious problems facing men. But I couldn’t get away from the very real sense that the reasons things were so bad was that it was our fault, and that if we were men who were just different than the creatures of the last several thousand years the world would be a better place.

Of course, a different view of the history of the world shows that, without those creatures, we wouldn’t even be able to have this conversation today.

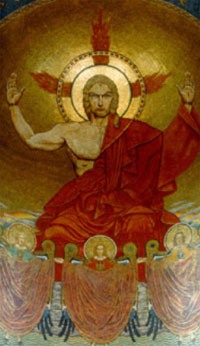

Let me end by reminding us of simple theological truths. God made us men and women, two different ways of being a body, but both equally made in the Image of God and both equally saved by the redemptive sacrifice of Christ. But they are made different for more than just reproduction. The simple observation that we intuitively understand our manhood or womanhood as something more than just a matter of our genitals is built in us for a purpose. In salvation history, Mary is exalted because of her faith and because she is a woman. The Incarnation is God-Made-Flesh for the salvation of all and he is also a man. These are not accidents. They are part of the perfection of the divine order.

I hope our current cultural moment might spur useful reflections on masculinity and I hope it will continue to shed light on practices perpetrated by men in the name of manhood that have nothing to do with a whole and holy masculinity. But in the end, I hope we can all appreciate men for being men and stop trying to make them into something else.

This needs to be read by more people than just those who are able to view this site.